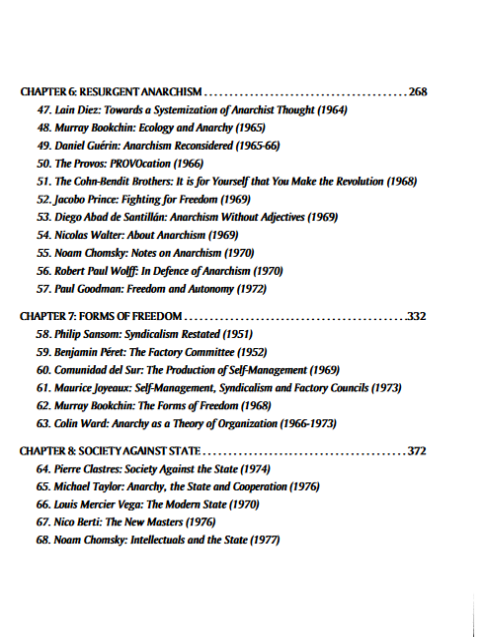

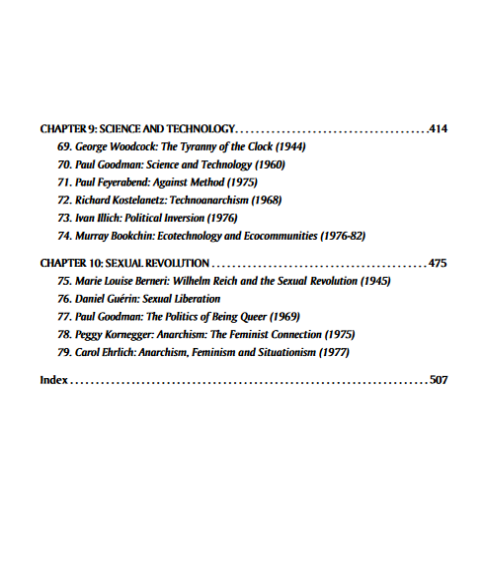

The New Anarchism 1974–2012

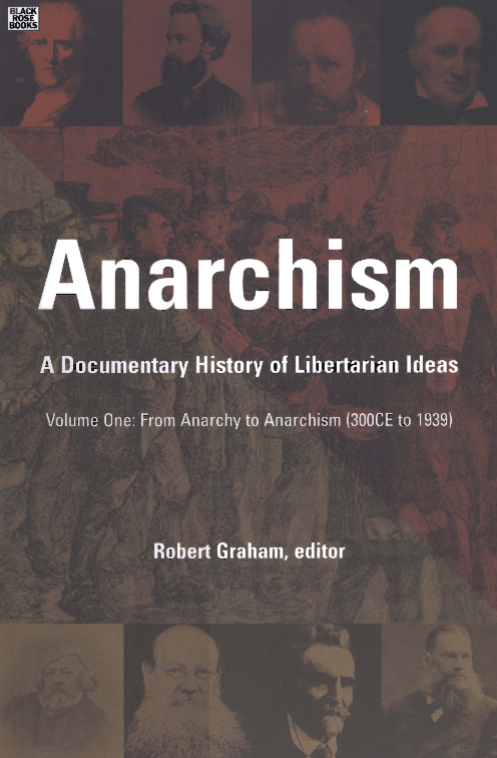

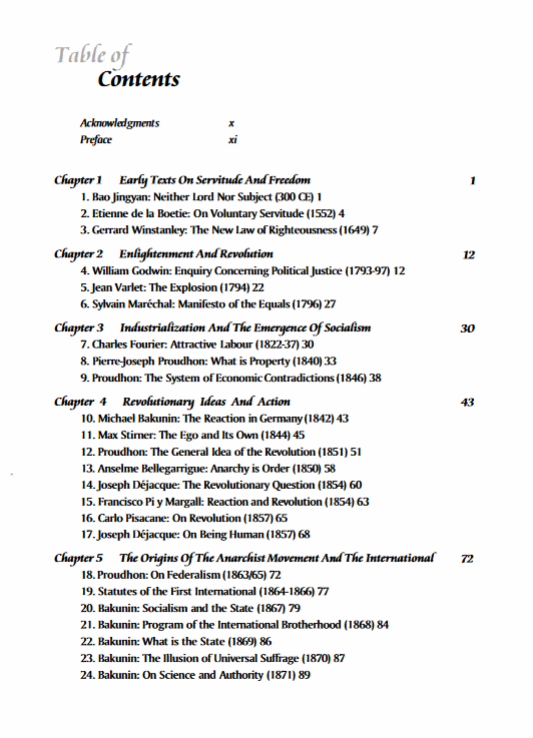

Volume 1 : From Anarchy to Anarchism (300 CE to 1939)

Volume 2 : The Emergence of The New Anarchism (1939-1977)

Author(s)

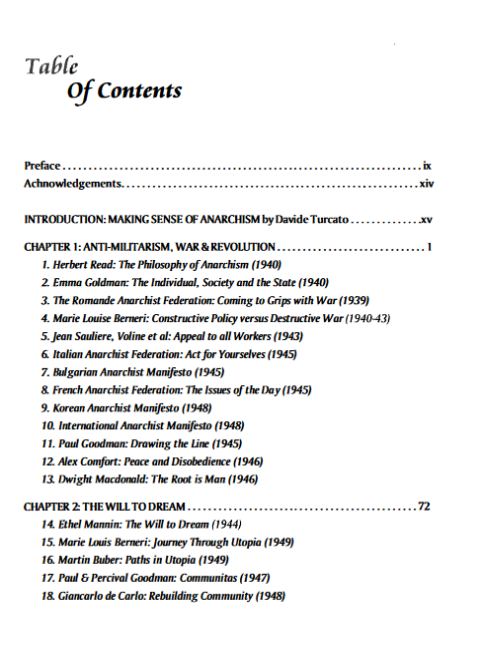

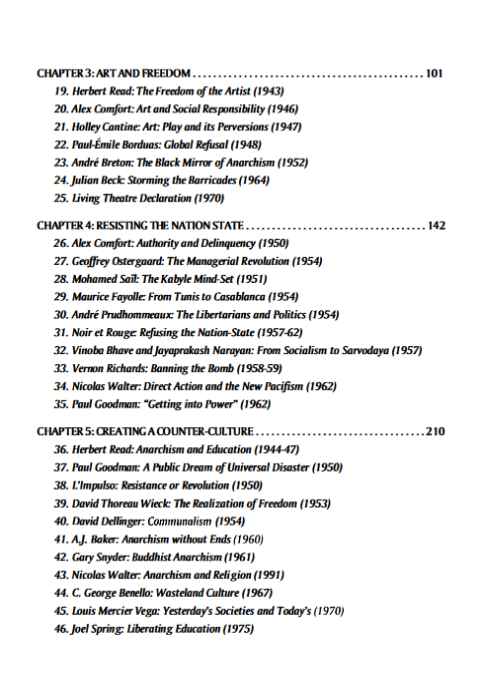

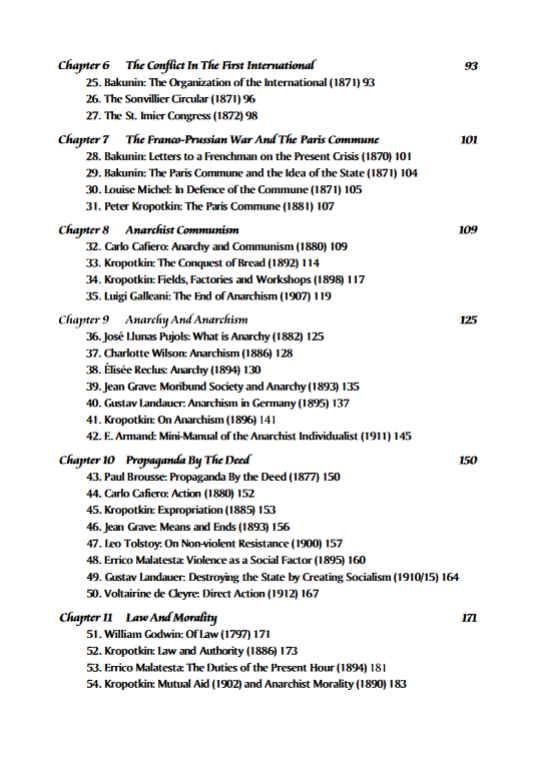

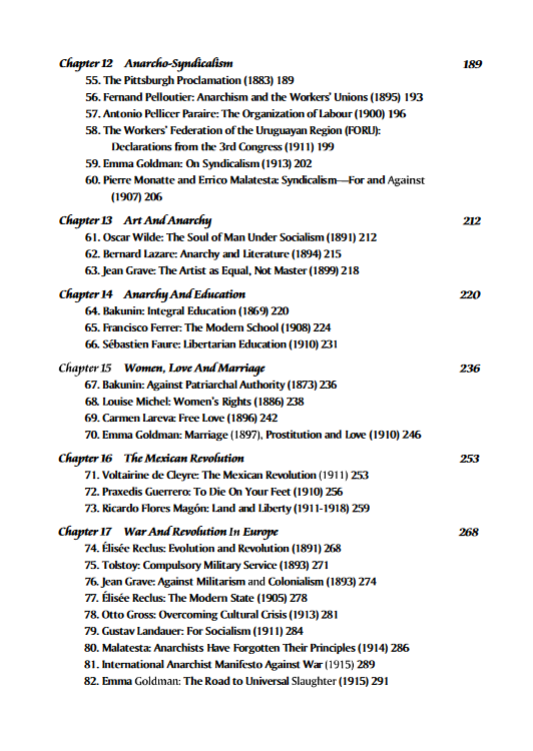

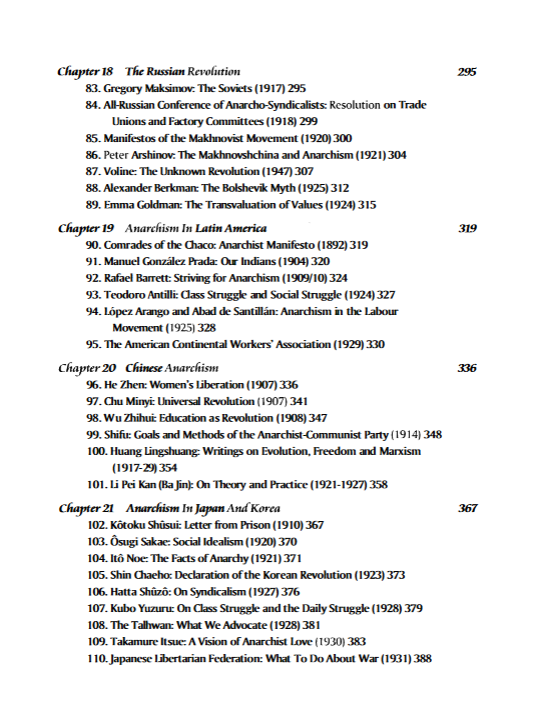

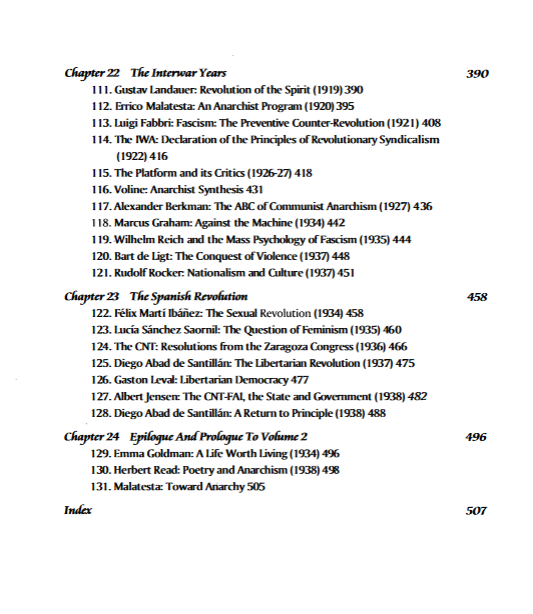

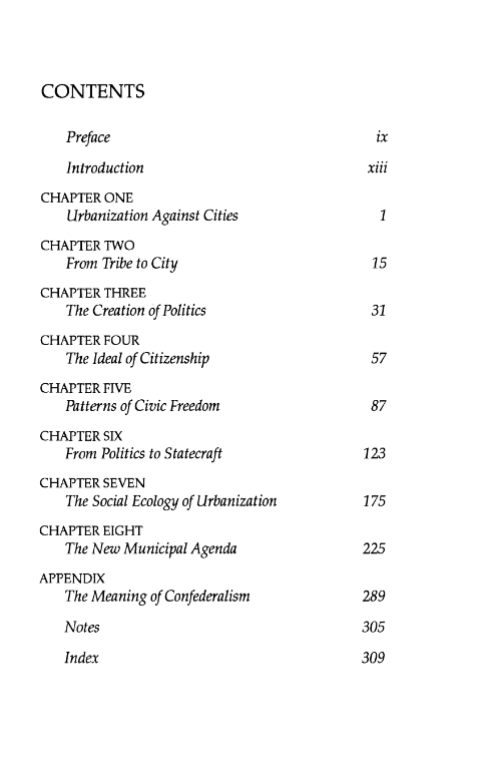

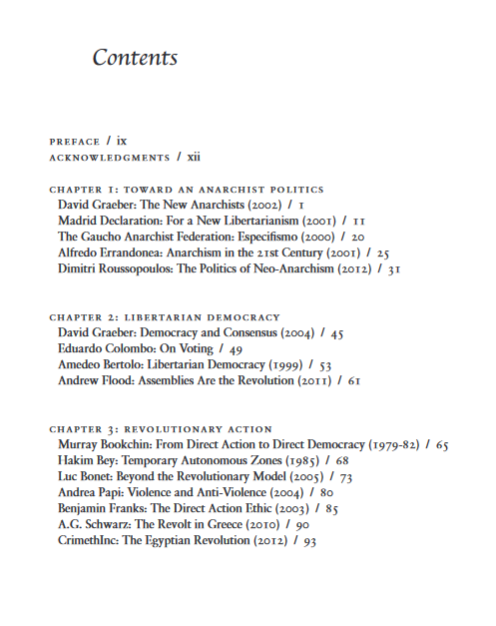

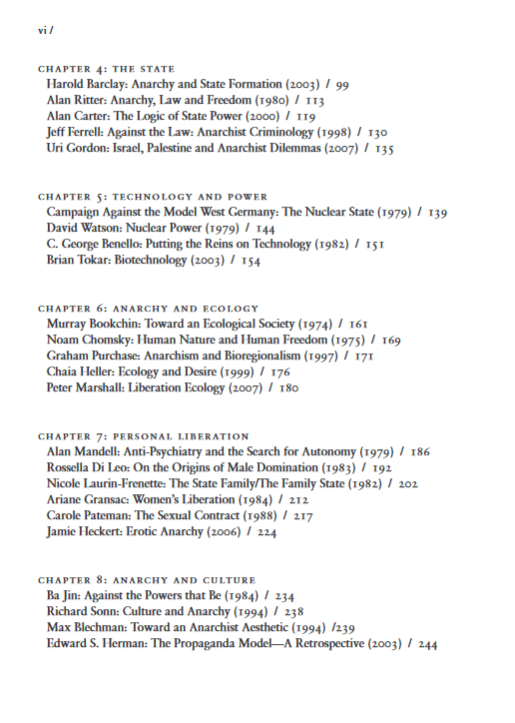

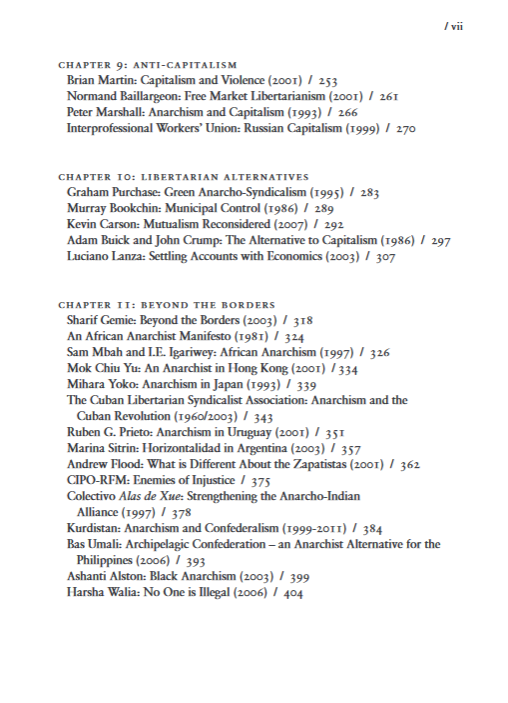

Contents

“Anarchy, a society without government, has existed since time immemorial. Anarchism, the doctrine that such a society is desirable, is a much more recent development.

For tens of thousands of years, human beings lived in societies without any formal political institutions or constituted authority. About 6,000 years ago, around the time of the so-called dawn of civilization, the first societies with formal structures of hierarchy, command, control and obedience began to develop. At first, these hierarchical societies were relatively rare and isolated primarily to what is now Asia and the Middle East. Slowly they increased in size and influence, encroaching upon, sometimes conquering and enslaving, the surrounding anarchic tribal societies in which most humans continued to live. Sometimes independently, sometimes in response to pressures from without, other tribal societies also developed hierarchical forms of social and political organization.

Still, before the era of European colonization, much of the world remained essentially anarchic, with people in various parts of the world continuing to live without formal institutions of government well into the 19th century. It was only in the 20th century that the globe was definitively divided up between competing nation states which now claim sovereignty over virtually the entire planet.

The rise and triumph of hierarchical society was a far from peaceful one. War and civilization have always marched forward arm in arm, leaving behind a swath of destruction scarcely conceivable to their many victims, most of whom had little or no understanding of the forces arrayed against them and their so-called primitive ways of life. It was a contest as unequal as it was merciless.

[…]

Anarchists and their precursors, such as Fourier, were among the first to criticize the combined effects of the organization of work, the division of labour and technological innovation under capitalism. Anarchists recognized the importance of education as both a means of social control and as a potential means of liberation. They had important things to say about art and free expression, law and morality. They championed sexual freedom but also criticized the commodification of sex under capitalism. They were critical of all hierarchical relationships, whether between father and children, husband and wife, teacher and student, professionals and workers, or leaders and led, throughout society and even within their own organizations. They emphasized the importance of maintaining consistency between means and ends, and in acting in accordance with their ideals now, in the process of transforming society, not in the distant future. They opposed war and militarism in the face of widespread repression, and did not hesitate to criticize the orthodox Left for its authoritarianism and opportunism.

They developed an original conception of an all-encompassing social revolution, rejecting state terrorism and seeking to reduce violence to a minimum.”

Robert Graham

Leave a comment below with a valid email adress (it will not be published) to request this book.