Author(s)

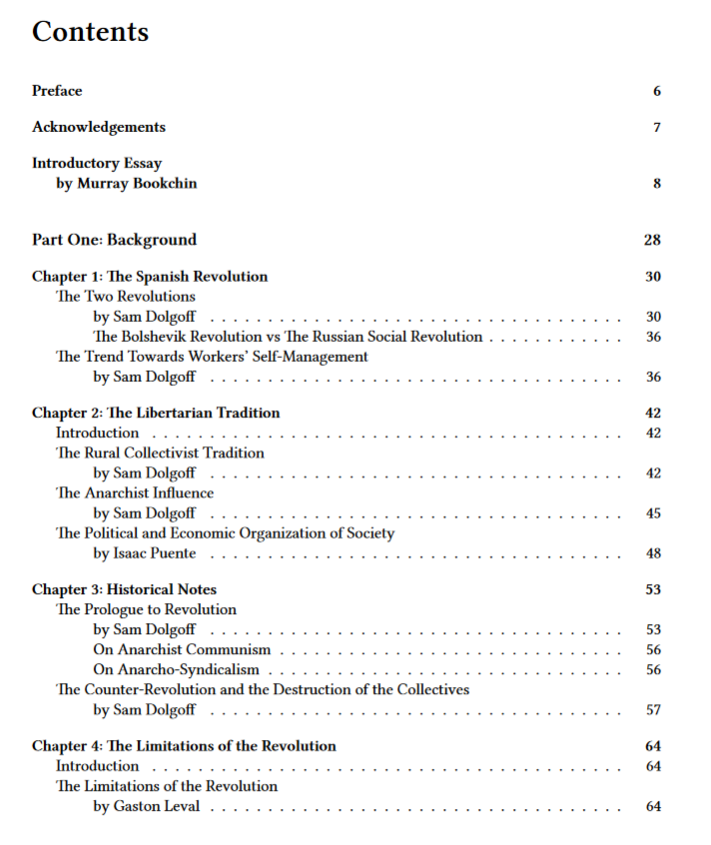

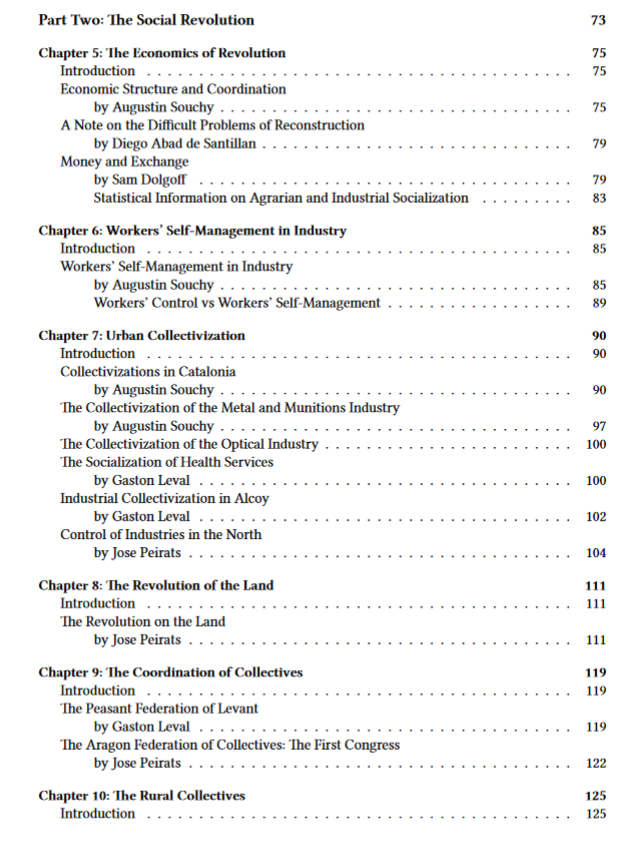

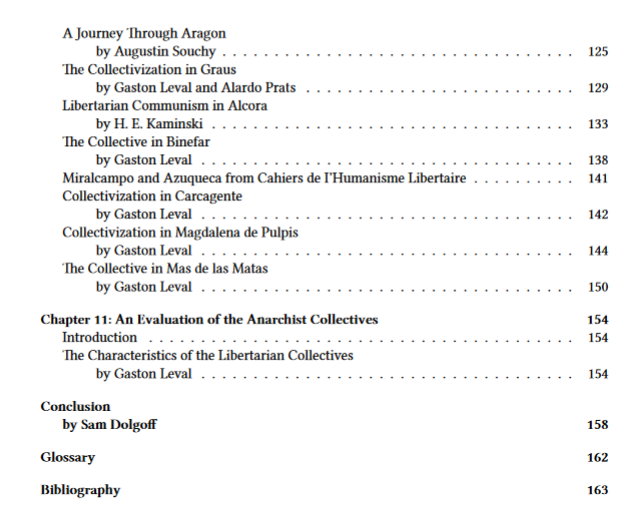

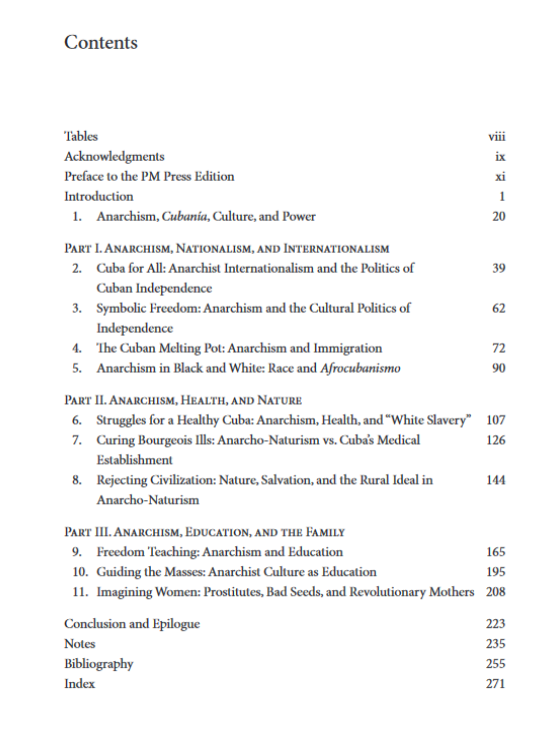

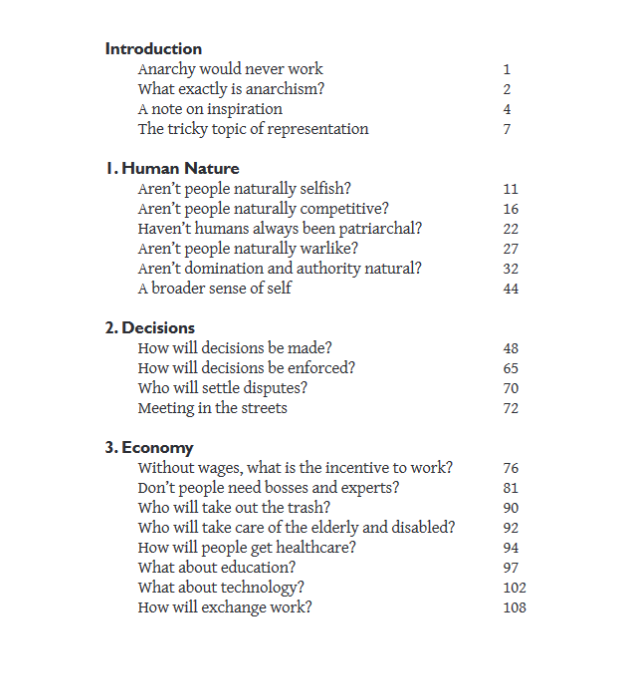

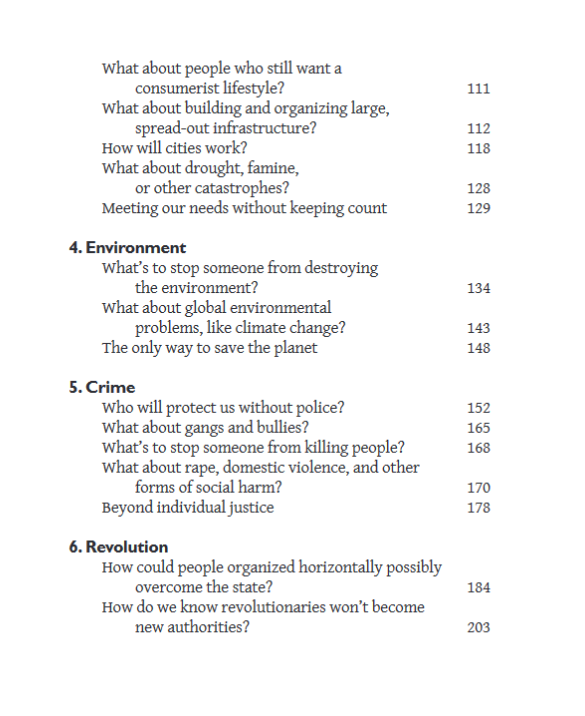

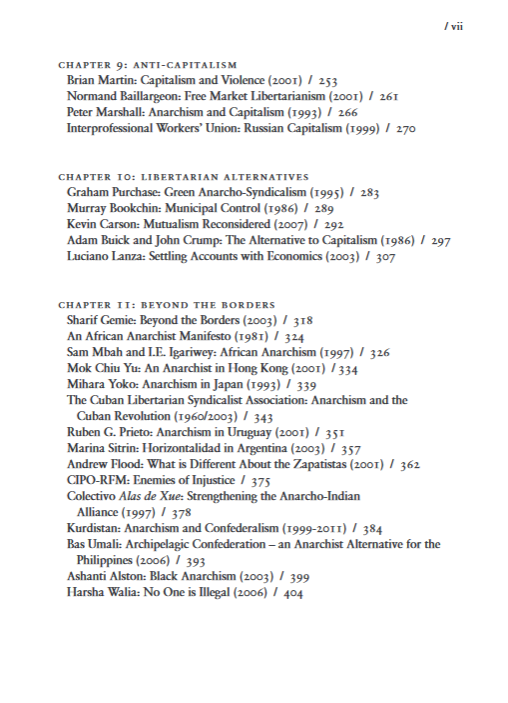

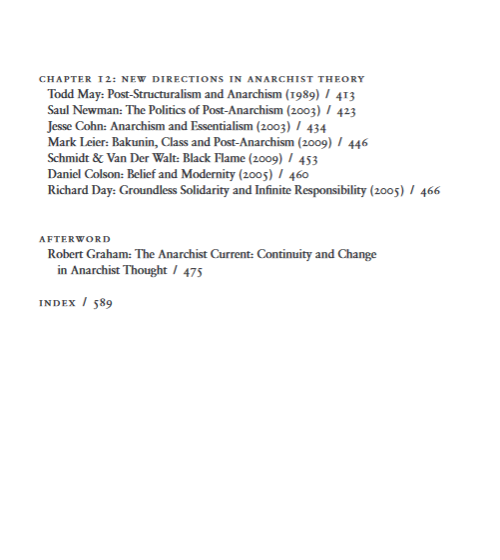

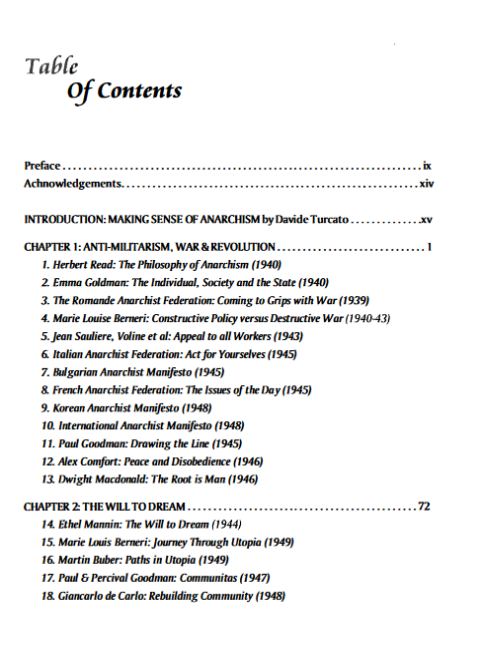

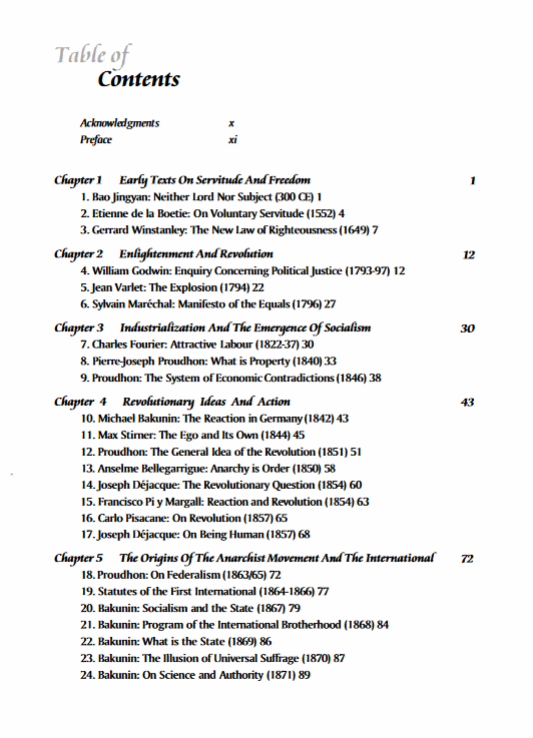

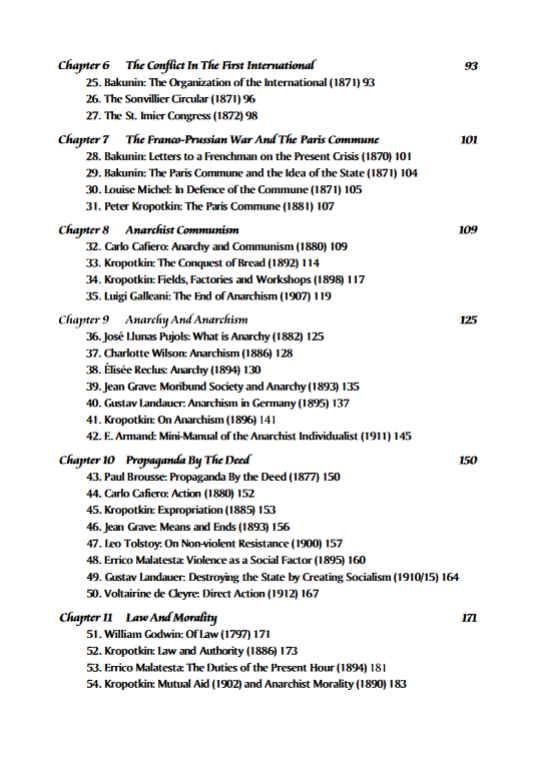

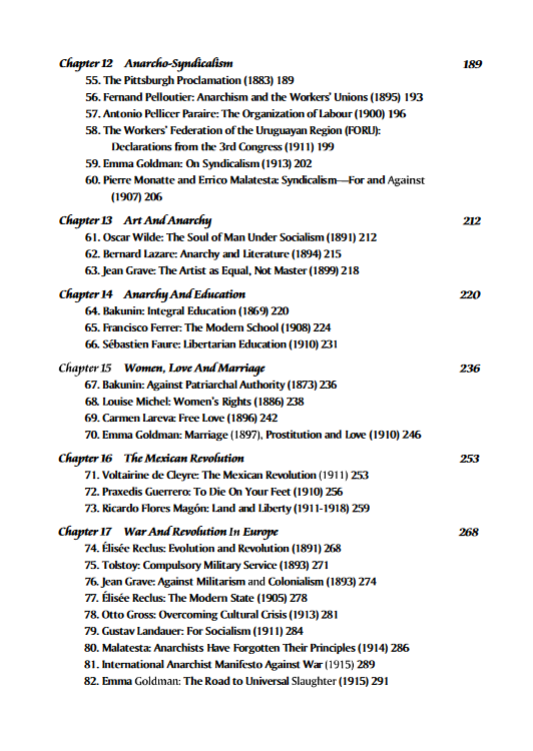

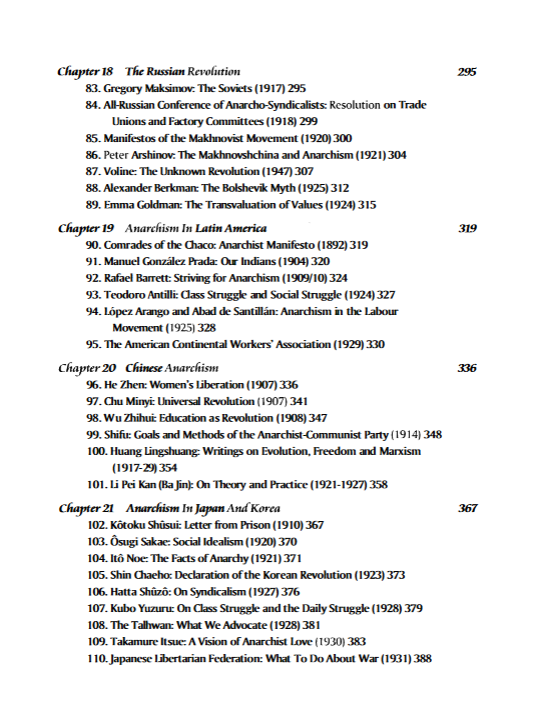

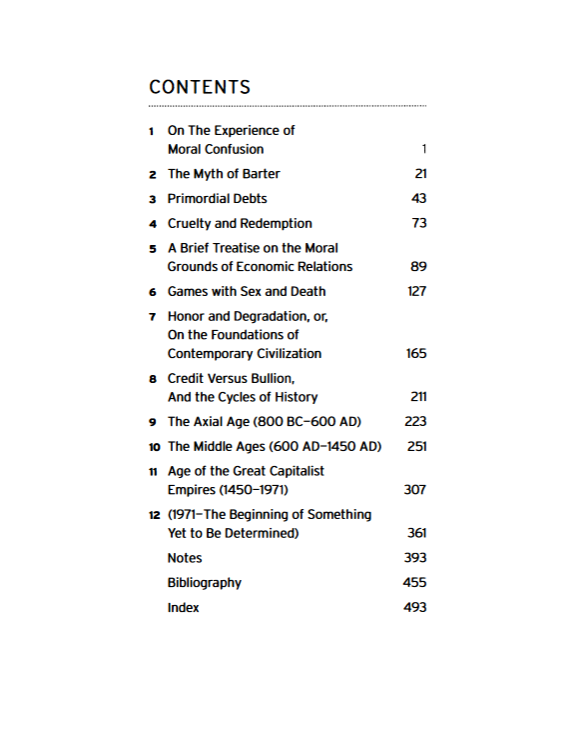

Contents

“The real history of markets is nothing like what we’re taught to think it is.

The earlier markets that we are able to observe appear to be spillovers, more or less; side effects of the elaborate administrative systems of ancient Mesopotamia. They operated primarily on credit.

Cash markets arose through war: again, largely through tax and tribute policies that were originally designed to provision soldiers, but that later became useful in all sorts of other ways besides.

It was only the Middle Ages, with their return to credit systems, that saw the first manifestations of what might be called market populism: the idea that markets could exist beyond, against, and outside of states […]

What we have seen ever since is an endless political jockeying back and forth between two sorts of populism -state and market populism-without anyone noticing that they were talking about the left and right flanks of exactly the same animal.

The main reason that we’re unable to notice, I think, is that the legacy of violence has twisted everything around us. War, conquest, and slavery not only played the central role in converting human economies into market ones; there is literally no institution in our society that has not been to some degree affected. […]

If this book has shown anything, it’s exactly how much violence it has taken, over the course of human history, to bring us to a situation where it’s even possible to imagine that that’s what life is really about.”

David Graeber

Leave a comment below with a valid email adress (it will not be published) to request this book.